Submitted by Ruthie Thompson-Klein, Equine Balance Hoof Care

I had to retire my best pair of nippers recently. Maybe it was time, but it was a nostalgic day. Those ergonomically wonderful GE 14s fit like a custom glove and took me through more than a decade of trimming. Between 2003 and 2014 I figure they have at least 10,000 horses on them – that’s 40,000 hooves. Not bad for three rebuilds on a original tool, whose design hasn’t changed since the early 20th century. Having to lay down the benchmark GEs got me thinking about nipper use – and misuse.

Trusty GEs, now retired to the spare tools box.

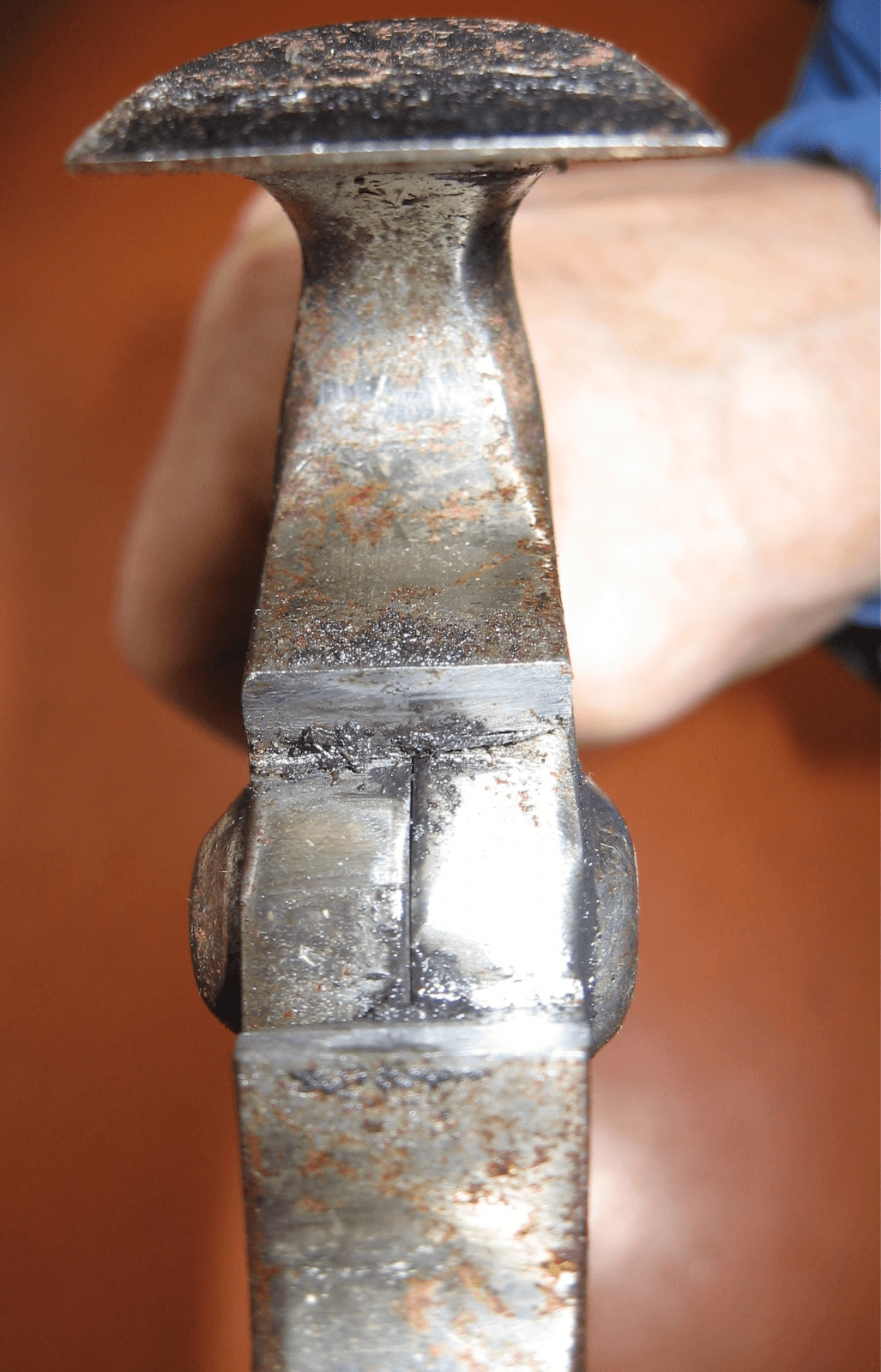

Nipper blade freshly sharpened.

Another tool rounded off from “walking” cuts around the hoof. Blade edge rounding is normal wear, but this cutting edge was used beyond routine maintenance and needs major work.

There’s evidence I used this tool far beyond its tolerance for an additional successful rebuild. What happened? High quality nipper blades are made of extremely hard chrome vanadium steel alloy making them strong, durable and resistant to wear. They are hardened by heat treating. The nipper reins (handles) are strong enough for leverage but can be a less expensive steel to manufacture. It is a balancing act; hard, thin blade steel is prone to chip and break under pressure or when struck, yet you can’t beat it for a long-lasting edge, which is heat-treated in a very thin layer 1/4 to 1/2” from edges of the blade. If you happen to hit a hidden nail this may prevent devastating breakage beyond this point. Speaking of hidden nails and nails in general, never, never, never use your nippers to cut or pull them out. Invest in an inexpensive pair of pull-offs or crease nail pullers.

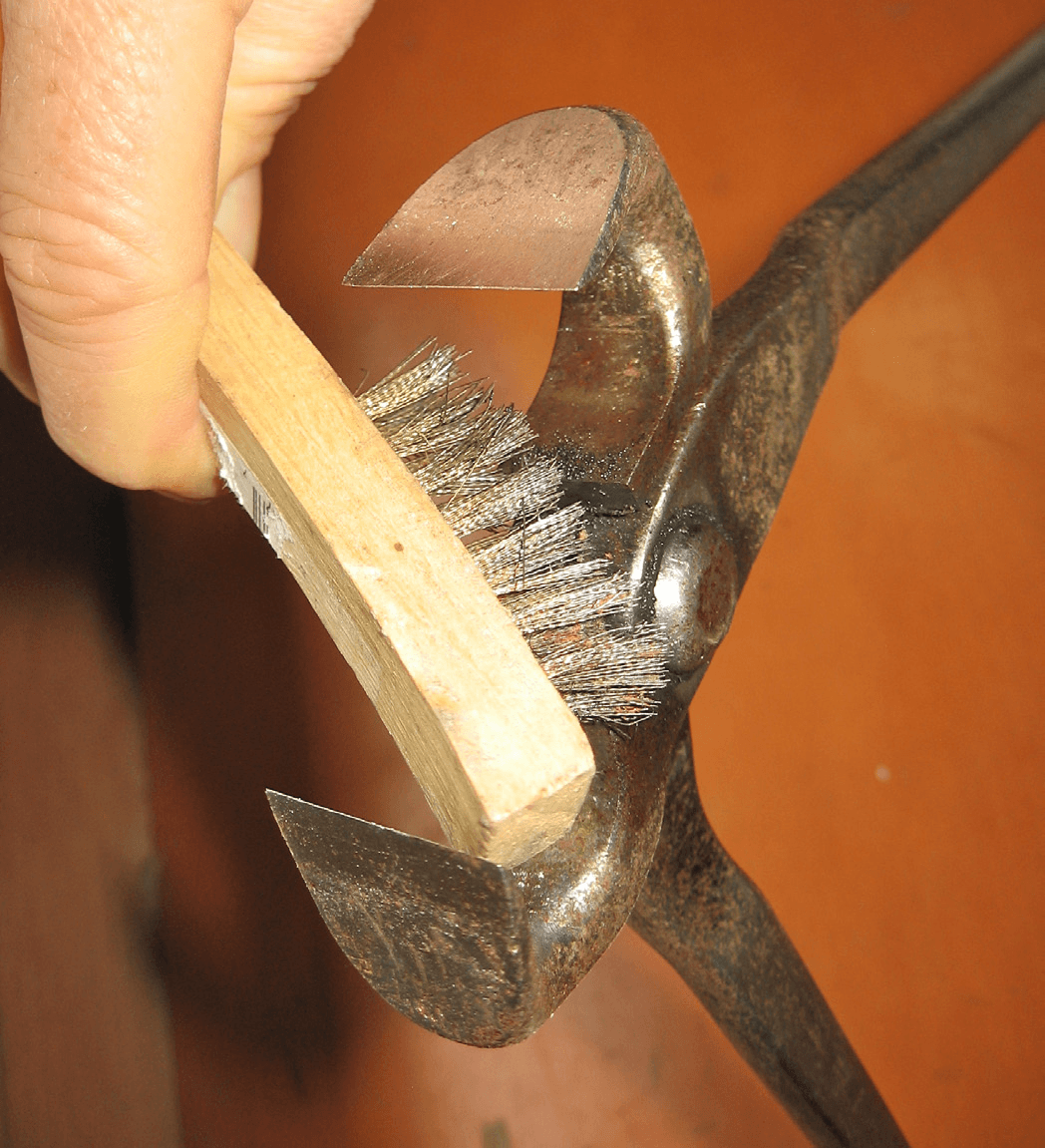

Remove grit and debris.

Clean the stops, AND the bottom of the horse’s foot before you take the nippers to it. Note the pitting and rust beginning to accumulate here.

Each time nippers are sharpened or rebuilt the blade edge and the stops must be ground down and realigned. Eventually, sharpening and rebuilding removes the hardened steel and you are left with softer metal that must be touched up more frequently. Enough rounds of this remedy and there’s not much bite left. Then you really are working harder not smarter; no more “one-rounds” on the occasional overgrown hooves.

Scrub those soles! Steel brushes can be used and sawed off as they wear out, until you’re left with a handy stick of kindling.

During GE 14s last few weeks in the rush of summer, I was feeling fit and strong. For long stretches I used muscle and tenacity instead of routinely maintaining my nippers to be at their sharpest once a week, or at least cycling in the spare pair, lower-quality tool. They cut hooves great guns, but I drove them beyond time for a rebuild. Pretty soon and very subtly, differing pressure on the reins drove the rivet in a less-than-360-degree motion, loosening the reins and quickly wearing the cutting edge. “Sure,” said my rebuild expert, “we’ll disassemble the tool, punch the rivet, grind the blades, forge everything back to square, and shine it up.” It was tempting. I looked at what was left of my favorite nipper. At half the cost of the original tool, a 4th rebuild investment would deliver a beautifully polished, sharp, and like-new nipper, but would it be efficient for day-to-day use and last long enough to be economical? Not this time.

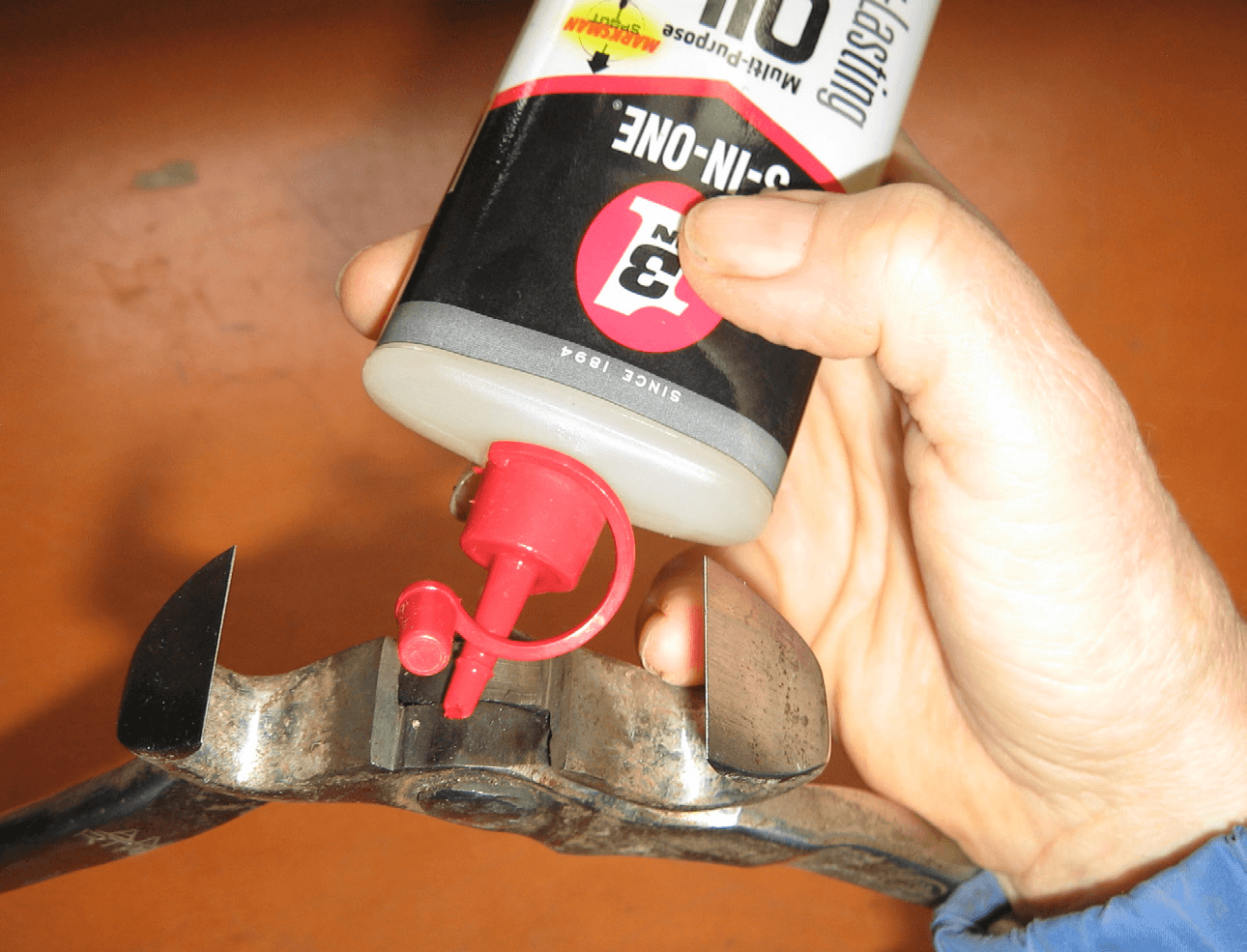

To extend the life of your nippers between sharpenings or rebuilds, get in the daily habit of cleaning and drying the tool, and storing it wrapped in a soft cloth (clean t-shirt rags are good.) Store it wrapped in a piece of old fire hose or its original packaging to prevent nicking and rusting. Check that the rivet is free from sand and grit, and working smoothly. Use an old toothbrush, light wire brush, or fine steel wool to remove rust pitting and debris build-up between the stops and below the rivet—this could be why your blades don’t cut cleanly. At least once a week, lightly oil the rivet area and rein shoulders. Work the reins open and closed to distribute the oil. I prefer LPS2 or 3-in-1 oil over aerosol products that contain quickly-evaporating solvents and leave behind a gummy mess. Take this step at the end of a work day to avoid debris collecting in the rivet.

After cleaning, apply oil sparingly and work the blades.

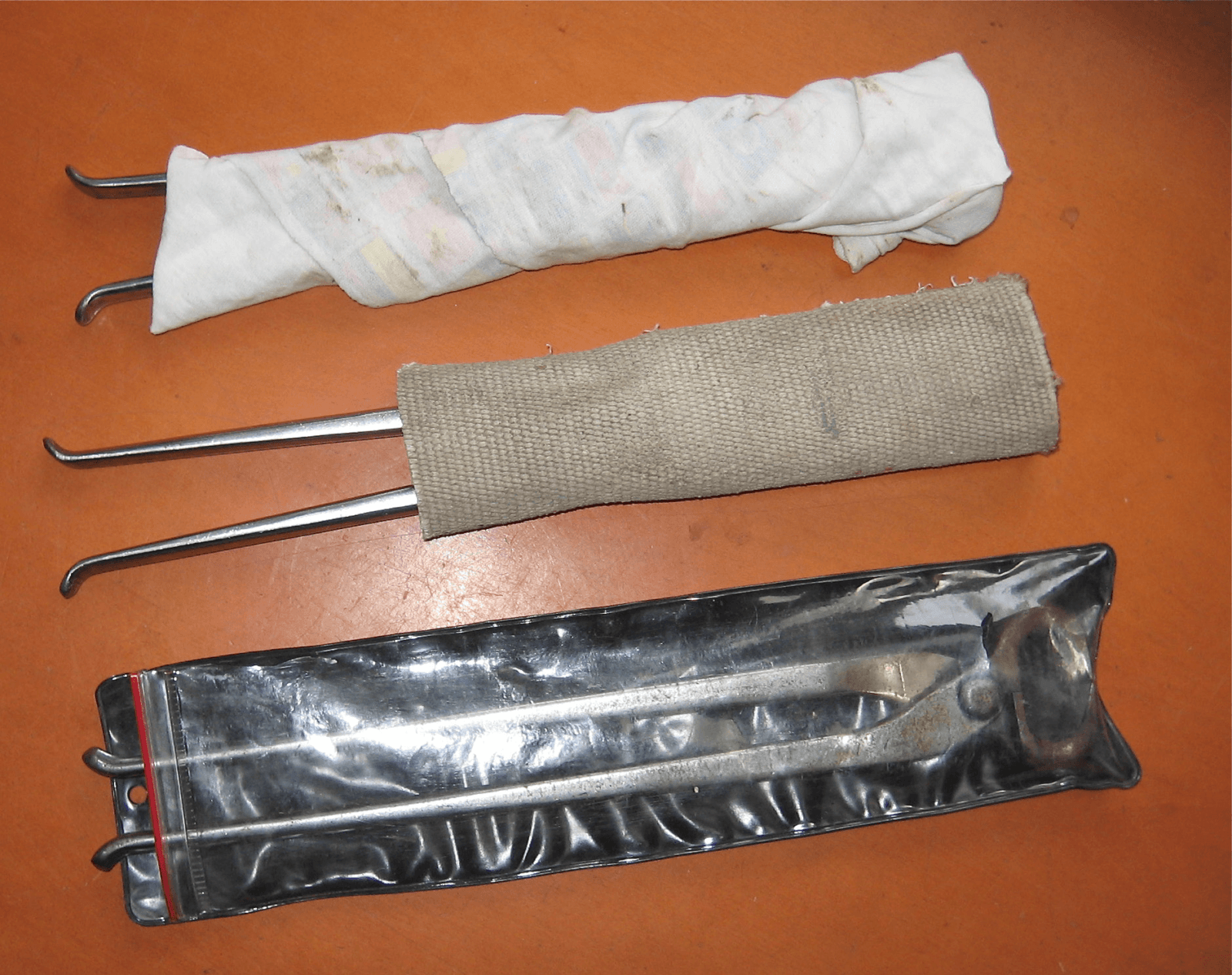

Storage options to protect blades from debris, nicks and rust.

I calculated average opening and closing my nippers approximately 585,000,000 times over a decade. This is why feel, balance and weight are important. Notice the difference in heft between nippers. A trade-off of control for leverage.

During trims, mind feet that have some hoof wall separation. Debris tucked away in the white line may harm your blades. Dirt, sand and small rocks are abrasive and will reduce the life of your nippers. If you have a spare pair of “they’re toast” nippers, keep them maintained for use when faced with an especially gnarly job or to make modifications on hoof boots and composite shoes.

Beyond day-to-day maintenance, sharpening is a subject for more detail. Beyond touching up the blades with a light sharpening from the inside, I recommend professional sharpening. Let someone else do it unless you are quite practiced in the art. Here’s where that “toast” pair can help hone your skills.

Enter a new favorite nipper: Lopez 14s, and renewed dedication to tool care. Here’s hoping for a long-lasting relationship.