In Part 1 of this blog, I discussed how hoof resection can be difficult to clearly define amongst hoof professionals because there are many opinions about what they involve.

The key message from that blog was this:

“However you define resection, two ideas seem to be consistent in the word’s common use:

1. A resection implies an invasive procedure.

2. A resection references a therapeutic situation needing intervention.

These ideas, and the sometimes blurry line between what lies in the farrier realm versus the veterinary realm, mean resections carry a a lot responsibility. The responsibility knowing when, why and how to do them; and the responsibility of who should do them in what situations”.

– See more at: blog.easycareinc.com/blog/hoof-love-not-war/hoof-resection-isnt-a-dirty-word3a-part-1

I’d like to share here a couple of situations I’ve been in where resections were required, how they were handled and why. Warning: some images are graphically intense, so scroll down at your own risk.

The first scenario was one where a foundered horse was referred to my care because the local farrier was out of ideas to help the horse. The right front foot on this horse was worse than the left front, with the hoof wall showing a fair bit of detachment from heel quarter to heel quarter:

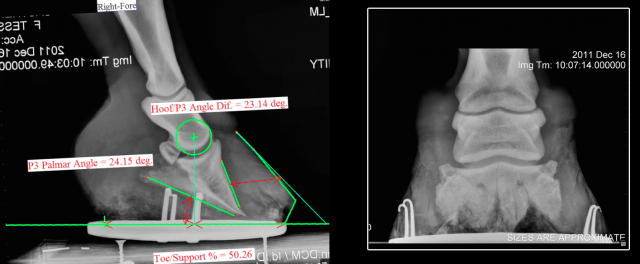

Here is the radiograph to go with the foot at this time:

After discussion with the veterinarian, we agreed that the detached wall needed to be resected. I felt comfortable removing the wall without on-site veterinary support as it was already detached and most likely keritanized under the wall. The veterinarian was happy for me to do the work and the horse owner was on board with our recommendations. Casual photos after the resection:

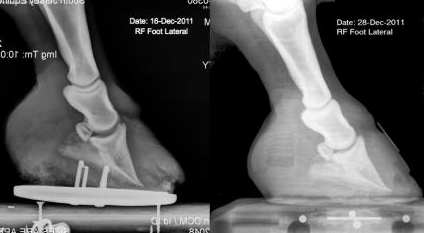

The exposed foot is insensitive laminar wedge, meaning it has no blood or nerves. Here are the photos and X-rays of the horse after the resection:

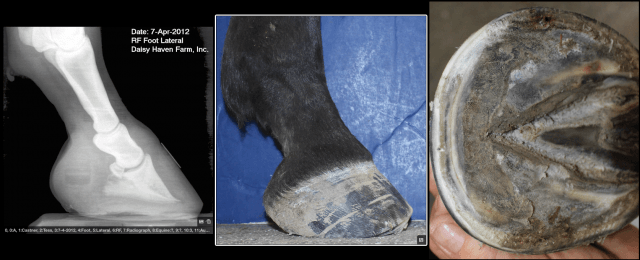

Here is how her foot healed after the resection just four months later:

To see more about this horse’s entire case study please see: http://www.thehorse.com/articles/33167/rehabilitating-horses-with-ems-associated-laminitis.

That situation was fairly straightforward and easy to determine what needed to be done and who should do the work. However, here is another scenario that wasn’t so clear:

I received a desperate call from a horse owner, their horse had foundered badly in all four feet. The local vet and farrier had given up on the horse and euthanasia was recommended. The owner was hoping I’d have ideas that would help the horse before giving in to euthanasia. When I saw the horse I was encouraged by his bright demeanor despite having P3 penetrate his soles on his hind feet, and agreed to work on the horse. Here is the left hind, the worst of the four at my first visit:

Over the next few months, the horse did very well, gaining sole, healthy new growth, and becoming more comfortable overall. My biggest concern was the medial side (inside) of the left hind foot. It was pinching in at the coronary band, and growth there wasn’t coming. Here is the medial side of the left hind foot when I became very concerned:

I knew that we most likely needed a resection of this section of wall that was folding. However we didn’t have any veterinary support. I had a decision to make:

1. Did I go ahead and resect the wall knowing I could get into sensitive tissue? This was not an idea I was comfortable with.

2. Did I wait and see if we really needed the resection?

We decided to give it a bit more time. However it was quickly apparent intervention was needed. Here is how that wall changed over a two-week period:

There was only one solution I was happy with: we needed a veterinarian who would help us with the resection and follow-up care. We decided to bring the horse to Daisy Haven Farm and work with our farm vet, Dr. Mark Donaldson of Unionville Equine Associates in Oxford, PA.

The resection was done as a team effort between Dr. Donaldson and myself, and went very well. Here is the foot with the wall removed where it was folding. The wall covering the coronary band had detached and cut into the soft tissue of the pastern. Notice there is no blood in the resected wall in this picture.

It wasn’t until the last piece of wall from under the swollen tissue was removed that the foot bled in this area:

This is the piece of wall, including the coronary groove, that was the last piece removed from up under the swollen pastern.

Here is medial side of the left hind foot after several months new growth:

What would you have done? Intervened earlier? Recommended euthanasia? Turned the case over to another farrier? In both of the cases I’ve shown here, the resection was a critical step in getting the horse’s foot healthy.

We each have to make our own decisions about how to handle situations like these. For me, the only way I know how to safely and successfully do this work is to be a team with the veterinarian, horse owner, and any others involved in the horse’s care. Who does the actual work on the horse should be a team decision. As long as everyone is on the same page with a clear plan, you will be successful in helping horses when resections are needed. Hopefully you will feel a little more confident in how to approach potential resection situations, as a team, when you come across them in the future.

For more information on Daisy Haven Farm, Inc. please see DaisyHavenFarm.com and IntegrativeHoofSchool.com.