I never did formal riding in any discipline, but the topic of “collection” is one that comes up (and I’m not referring to my tendency to hoard horses). WARNING: This is A view on collection, not the be-all, end-all reference article for all things equitation.

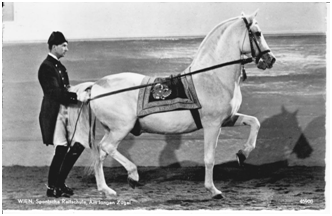

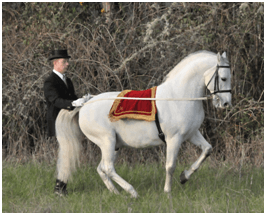

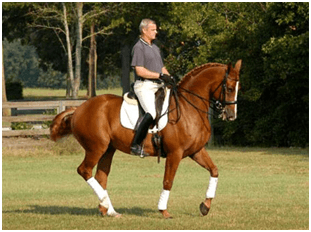

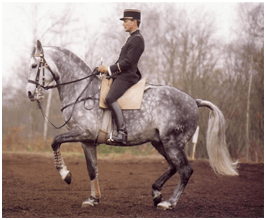

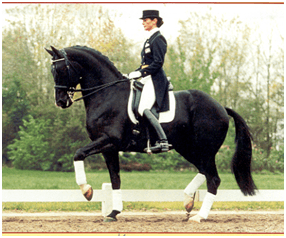

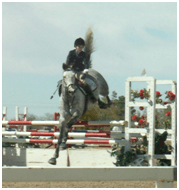

What I appreciated from an anatomical view, was the amount of elevation and elasticity the horse put into his movement. His potential for action was put into becoming lofty and potentially explosive. In a wild horse fight, explosive might translate into a barrage of attacks. In a controlled explosion, we are seeing extended trots and jumps of massive heights being cleared. But in every picture I included here (and many more that I found) you can clearly see the horse engaging that hind end, tucking his rear under him so that he was ready for any variety of movements. It’s not surprising to see horses do this at liberty, as they are deciding on a whim where they want to move next. Dancing by themselves in their pastures, racing imaginary friends or shying away from horse-eating butterflies.

The deep digital flexor tendon and the suspensory ligament are huge players from the ground-up approach to collection.

The balls of our feet are important to our ability to spring. Try this: Do a jumping jack. Now lean back on your heels and lift the fronts of your feet off the ground. Do a jumping jack starting and landing on your heels. You will have to exaggeratedly absorb the shock of your jump with your legs, back and torso. Now do it from the balls of your feet. Easy peasy.

So while a jumping jack can literally be the act of “jumping out and back in”, knowing how you start and finish it and where the power comes from will change how easy it is and how graceful it looks. Sort of like collection. In fact, you can’t do high knees, jumping jacks, side shuffles or out-and-backs without using the balls of your feet. If you tried to do it with your heels, you would feel quite ungraceful.

Now, if a person was jumping from their heels and landing back on their heels, I could say,

“Higher. This time don’t make so much noise when you land, it was clunky.” and you could practice.

“More arms, you are not using enough arms. You look clumsy.” and you could practice.

“Your feet need to land further apart. Try again.”

“Your knees are wobbly, tighten them up.”

“You are moving your torso too much. I see others doing jumping jacks and they don’t have such movement.”

And on and on. What I really should say is, “You are launching and landing from your heels. Start from the ball of your foot.”

Similarly, I’ve seen horses “fitted into frame” for collection, instead of corrected from the ground up. “His legs should pick up higher, he should be more animated, his headset is not right, his back legs need to more lift and to be more under him.”

I’m not a student of dressage, so don’t string me up, but I tried finding two nearly-the-same images of horses doing a piaffe, riderless. The horse on the top clearly has lovely height to his feet, but nothing about his “collection” looks “collected”. He looks less likely to launch forward or sideways and more likely to just start walking after he’s too tired to keep doing it. The horse on the bottom is in a slightly different stride of the move, so it’s hard to say how high his hooves move, but would that really be the standard to judge him by? Look at his whole figure! He is collected, waiting to move at a moment’s notice, ready to launch forward into men wielding swords or wheel to the left or right to carry an owner to safety or to leap over a barricade and bolt up a mountain. All the while the horse on the top is doing a piaffe as gracefully as I could do ballet while pregnant. He’s waddling and strung out and all he knows is, “Tom wants my feet higher and my head just so. And I need to look exuberant while doing it. Gosh collection is hard!”

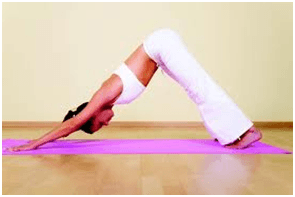

It’s like doing downward dog wrong. You don’t get better at practicing it wrong, you just get better at doing it incorrectly. Yet, there are higher yoga poses to attain, which depend on your being limber enough to correctly do downward dog. You see where I’m going with this? Your chance of lucking into a Flying Monkey Spider Crane Position while feeling nirvana are slim to none.

And just in case you’re not all “Namaste” with me, the girl on the top is doing it right. Her head to her butt is a straight line, You can see her line break at the hip in a clean cut. The girl on the bottom doesn’t have a line from her head to her butt. You can see the small of her back is bending so that she “can” do the position. This would all be fine if downward dog was the end of your yoga path. Visibly, she’s close, structurally, she’s not. To go to upper levels, you need the basics to be correct.

As soon as she tries to go on to the next advanced movement, she will struggle. When your back is humped, getting that open chest twist is nearly impossible. It’s like slouching and trying to open up your shoulders. It requires a lot of effort to do it wrong (which is super fun and rewarding). For some of us, the word “Yoga” is Sanskrit for, “Super-difficult, tortuous stretching”.

Good. Luck. With. That.

Entry level jumpers need to learn how to clear meter fences with correct form and build jumping musculature. Sloppy jumping at lower levels means you are never making it to Rolex.

I stumbled upon this video the other day. While Pedro Torres is a medalist for Spain and does World level dressage with this mount, look at his collection work put into action. This horse will blow you away.

While he’s running an obstacle course through poles, he’s doing flying lead changes. While he’s in a blank arena, he is also doing them. When you can see the correlation between movements that were trained for purpose, for a real life function, you can appreciate what you are looking for when merely testing those movements. It would be silly to take a horse and have it do flying lead changes when all it was doing was “memorizing” that every other stride needed to flip and not actually listening to his rider, wouldn’t it? As soon as you set a horse into real life application, he’d fall apart.

Let’s look at some horses that look “forced” when in collection:

Then I look at the body lines of these horses:

Again, we look at our nimble grey in those videos. He’s wound, bound and ready for action. He doesn’t care if the action is forward, backward, sideways or over a jump. The horses above look coiled, prepared, ready to do whatever the next command is.

So my first point, in all this rambling is: training with purpose, use and intention. Training to not shortcut. If you are training for a “look” alone, you end up with a tired pony who isn’t building each movement and will never reach the higher movements without a lot of strain.

And here’s my second point: There was a study done in England. https://www.facebook.com/EquitationScience/posts/10152231176856097?fref=nf

They took 20 Irish Sport Horses that were used for riding and dressage and videoed their movement. The selection had horses that had either been shod for 12 consecutive months or barefoot for 12 consecutive months.

You can read it (and you should) but the summary conclusion is that shod horses had diminished stride length, increased concussion and had more tendon flexion than their unshod counterparts. Unshod horses had less concussion, longer strides and their tendons had to flex less to absorb impact.

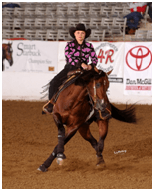

So, if shoes don’t give you an advantage, but DO shorten stride length and cause the tendons to have to “give” more to support your horse, then give barefoot equitation a try. Lateral movements would be a cinch if a horse had an ankle like ours, but he doesn’t. He’s going to need his hoof to be his first point of shock absorption. Reining, barrels, dressage, jumping etc. all athletic sports have lateral movement.

We pick the right saddle, the right bridle and the right pad because they fit our horse and enable us to communicate more clearly and make our horse’s job easier. It only makes sense to make sure he’s able to the job from the ground up.

Or what Stacey Westfall does (I could watch her bareback and bridles demonstrations all day!), we can try to start our horses right, continue to work with them with purpose and hope they have a saddle (or not), a bridle (or not) and now…. shod OR NOT, to be able to better perform what we ask of them.

Holly Jonsson

Director of Sales

Through a lifetime of “horse crazy” and the fortunate experience of riding nearly every shape and size of horse, I got to see a wide array of hoof shapes and sizes. No Hoof, No Horse is very true to me. I want to ensure that horses on every continent have a variety of footwear to pick from, to ensure the best match is found. I want your partner to be happy from the ground up!