Endurance riders love a BIG trot. When looking at your upcoming superstar or admiring how your favourite horse trucks down the trail, nothing excites more Oohs and Aahs amongst endurance riders than that big trot. Many endurance horses, maybe yours, undertake most of their competition miles in that big trot. I would like to suggest there are a number of reasons why the big trot is not the be-all and end-all and that more canter should be included when covering distance, for a number of reasons including:

1. Energy efficiency;

2. Scapular inhibition; and

3. Lumbar/sacral strain.

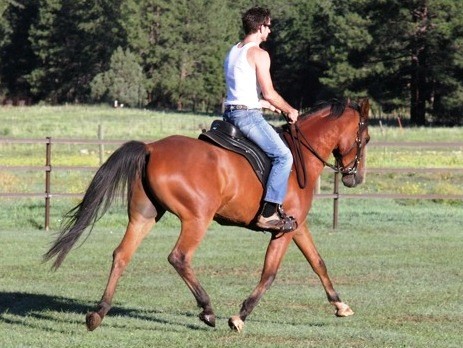

This horse clearly demonstrates all the hallmarks and pitfalls of a big trot. Although momentum plays some part in his extravagant movement, this degree of limb hyperextension requres a significantly higher degree of muscular effort than would a more modest stride. His scapular (the large bone of the shoulder) is forced through an excessive range of motion with the scapular cartilage (at the top of the shoulder blade) hitting the saddle with each stride. His hind legs are widely separated – one forward, one backward – placing excessive strain on the joints of the pelvis/sacrum and the lumbar region of the back. For these reasons, his neck is short, his back is hollow and his hindlegs show minimal joint flexion at hip, stifle and hock; instead they swing, pendulum-like, outside the path of the forelegs.

1. Energy Efficiency

When your horse moves in hyperextension, that is lengthening more than provided for by momentum, excessive muscular effort is required: extended gaits are not energy efficient. The further forward the hoof lands relative to the body mass, the more braking action occurs. Generally, a hyperextended hoof also stays on the ground for a longer period of time; tempo decreases as stride length increases. Muscular effort is required to overcome both the increased braking action and the inertia of the grounded hoof. From an energetic point of view, for most horses, any work faster than 15km/hr (ca 9mph) should ideally be performed at the canter rather than trot.

Unlike the canter, the trot lacks respiratory coupling. The up and down motion of the canter causes the substantial mass of the digestive system to move backward and forward within the body cavity with each stride. This piston-like motion activates your horse’s diaphram, automating the breath with each stride, with almost no effort – an incredibly efficient way to move. The only time cantering is less effecient than trotting at fast speeds is travelling up very steep hills. Here, gravity works to push the digestive tract backward so respiratory coupling is not activated and the tempo of the canter is too slow to provide sufficient oxygen with each breath/stride and your horse quickly moves into an anaerobic work state. Although breathing at the trot requires more energy, your horse can choose to take a breath with different numbers of strides: increasing available oxygen and removing carbon dioxide.

2. Scapular Inhibition

This photo shows what happens to your horse’s shoulder when he trots with lengthened strides for extended periods of time. Note the bulging scapular cartilage at the top of the shoulder blade from repeated trauma as it impacts the saddle and the ‘hollows’ immediately in front of and behind the wither as the horse tries to protect his shoulder from bruising by the saddle.

The shoulder of your horse has no bony attachment to his body: rather, his thorax is supported between his fore-legs within a sling of muscle and connective tissue. As a consequence, the shoulder blade (scapula) is very mobile, with a wide range of motion. As your horse extends his leg, the scapula rotates backward: the greater the extension, the greater the degree of scapular rotation. The top of the scapula consists of a cartilagenous area and this will commonly impact against the front of the saddle.

Over time, repeated impact results in congestion of the scapula cartilage – trauma. In an attempt to protect himself from more trauma, your horse braces the muscles around the top of the shoulder – in particular the trapezius muscles but many of the muscles of his topline are impacted – giving rise to the classic endurance musculature where there is a dip in front of the wither at the base of the neck and a hollow behind the wither. Flexible and semiflexible saddles that allow the scapula to move underneath them without impact greatly reduce this issue and, combined with appropriate body work and body-use reconditioning allow this issue to be addressed and enable normal scapular function.

3. Lumbar/Sacral Strain

In the trot, your horse’s hind-legs are widely separated with each stride, with one hind-leg reaching forward and the other hind-leg reaching back. The pelvis and in particular the sacrum come under increasing stress with increasing stride-length at trot. In this configuration, it is difficult for the lumbar region of the back (the area directly under and behind the back of the saddle) to remain supple as one side of the horse is in extension while the other is in flexion. Inevitably this leads to lumbar strain and pain. Again your horse braces his muscles in this area in order to protect himself from lumbar pain, leading to further back stiffness and hollowing.

In the first picture the hind-legs are widely seperated in the lengthened trot, which, over time, leads to sacral strain and lumbar bracing. In the second picture the hind-legs move closely together at the canter enabling the sacrum and lumbar region to tuck freely, mobilising the horse’s back.

These three issues inevitably combine – the result is your endurance horse has a hollow back.

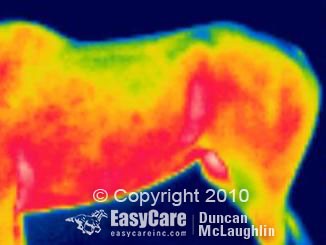

The photo shows back and hind-quarter musculature typical of endurance horses, though this is a more extreme example than commonly encountered. For the reasons discussed here, rehabilitation requires that big trots are totally avoided. The thermograph of the same back shows how extensively circulation through the musculature has been disrupted. Note the relatively cold area (green) where the saddle sits as the muscle fascia has thickened. The lumbar area (immediately behind the saddle area) is very restricted with little blood flow whatsoever (green and blue) and has put excessive strain on the sacral tuberosities (the pointy lumps at the top of the croup). A horse with this degree of muscular shut-down will not be able to use the hindquarters in any meaningful way.

By all means, use all the gaits available to you when training and competing your horse. Just dont get bogged down with the idea that a big trot is the be-all and end-all. Break the trot up with canter wherever appropriate and your horse will go much farther for less effort.

Very interesting! My little arab mare ‘found’ her canter last season, and now we do most of our ride in that gait, and trot for a rest. Her back is as strong as a plank and she has a med-low head carriage, and has never shown any soreness or problems at vet gate. I didn’t know we were doing the right things, and it’s good to know the anatomical background.

Thanks Dunc.

I will revise my belief:-)

Appreciate the explanation.

Totally agree about the photographer, tho!!

cheers

Jen

One of the things that’s important in all of this is for a horse is to carry themselves correctly — using their hind end, lifting the back and lightening the forehand. When the horse is head-high and hollow backed, as Duncan shows, they are putting an extraordinary amount of weight on the forehand, thus the leg injuries and lamenesses. Also, the hollow back is not meant to support the weight of a rider — you need the back lifted to provide proper support — especially over the distances we all travel. A horse doing a big trot "incorrectly" is much more likely to injur himself than a horse than a horse doing the same trot in self-carriage. Also, if the saddle is fitted properly, placed in the proper position on the horse’s back, and if the horse is lifting their back, you should not encounter any jamming of the shoulders. If your horse travels head-high, I would highly recommend lessons from a good instructor, to get your horse moving correctly. This will save a lot of wear and tear on your horse. Donna Snyder-Smith, Peggy Cummings, or other Centered Riding or Connected Riding instructors. I have learned tons from them over the years!

Naomi

P.S. Becky Hart, 3 time World Champ is a Centered Riding Instructor. And Rio had a big trot!

i learned alot thanks

Hey Jen, a couple of things. I think the main reason people like to trot is security. Trot is rhythmic and stable and makes riders feel safe. Canter is in three time which is not a natural rhythm for humans and the horse is much more mobile in canter and prone to move off target. When horses have difficulty in cantering it is never because they are ‘not ready’. Either the rider is causing problems or the horse has a biomechanical issue preventing an easy canter. With regard to the horse selecting the gait, personally, on my own horses, I would always choose the gait. As you know, I love the equitation approaches of both Richard Weiss and Manuela McLean. My idea is that I should select the speed/gait and direction/line and my horse should not deviate from that (actually this is just straight McLean behaviourism ;-), once selected the gait is maintained with rider biomechanics (straight Weiss biomechanics). My horse’s responsibility is to place his feet safely on the trail within the parameters of speed and direction (that is how my horses go so fast in the dark – I set the speed, they look after staying upright on the trail). Of course, this means the horses need basic stop, go and turn responses, and how many endurance horses have those?

Also, I am not saying never do a big trot – it is particularly appropriate when you know the ride photographer is around the next corner – just that over the long term it is not doing your horse any favours. Dunc

My poor husband. I am going to send this to him as he has a Morab with a HUGE trot and when we are out riding together, I am often heard to comment "just because he CAN doesn’t mean he SHOULD."

My younger horse has a healthy big trot but nothing like my veteran horse, and I can already see that he naturally takes better care of his topline.

Ditto all the comments re: cross training with dressage.

Enjoyed the article and photos.

–Patti

Hi dunc

Great stuff as always.

This reinforces a converstaion I had the other day where I stated that I believe the horse should be allowed to select their gait whilst I selecect the speed. My friends disagreed violently. I am inclined to think that a horse will know when to go into a more efficient gait before I do.

Sometimes I think we encourage the big trot because we think the horse is ‘not ready’ for canter, when it is really the opposite.

Thoughts?

cheers

Jen

Tks Duncan this goes a way to explaining the mounds on Lani’s shoulders.She was her own worst enemy as canter never was her natural gait of choice and I had major problems getting her to canter years back. She was broken in at 6 yrs of age after I bought her. New purebred arabian Karri always offers canter and I will encourage this more.

Thank You, this has been our philosophy for years. I believe that is what help contribute to Excalaber’s +/ success and retire 100% sound! We actually train so that we use the canter at apx 12mph and make sure to use both leads!

Having a young horse with a big trot, this article is the most timely I have read in recent years. So many endurance riders envy the big-trot horse. Now I will monitor the distance I allow my young horse to use his big trot and add in more cantoring. Thank you very much for this useful information.

Great article, I agree 100%. Nice to see the evidence to backup my way of riding/thinking.

What a fantastic article Duncan. Thank you for sharing this information with us. When i first started endurance, all you use to hear from everyone was "dont ever canter as your horse is just trying to be lazy, you must always trot and extend trot for endurance". I soon found out after my horse kept wanting to canter, was that she was more comfortable cantering than doing extended trots everywhere – now i know why! Thank you.

I have been a trainer for 30+ yrs. in the eventing, dressage, hunter/jumper disciplines. I have added endurance horses to my training program in the 90’s. One particular woman, who sent me her Arabs, for the winter training, had much sucess with there ability to keep a lovely topline. I used cross training. This is the training that I used for event horses. The emphasis on the endurance horses was "Dressage". Lots of long and low. Plenty of latteral work. By the time I was done with them these horses were solid 1st level horses, with 2nd level movements. I am also a equine sports massage therapist. I paid special attention to the cartilage at the shoulder. I adjusted saddle pads according to the needs of the horse. Shimming areas that needed to relieve preasure points. The end result was horses with lovely round toplines, which provided good muscle tone to support "The Big Trot". I think endurance riders need to be educated on proper flat work to avoid these typical "Endurance Topline".

Duncan, this information reinforces how I have thought (and trained) for many years. That ‘big trot’ is not a good thing!! And as Christoph also states, the damage to tendons from the ‘flick’ at the end of a trot stride can also be a problem. I much prefer a working trot combined with plenty of pace changes. Great article… thanks!

Duncan, thanks for sharing this. It is very valuable information. Furthermore, extented trots are straining suspensaries and tendons much more than a canter. A horse naturally will always canter before trotting. When observing horses on the pasture or in the wild, they will either walk or canter. Very seldom will you observe a horse trotting voluntarily on their own. Horses will select automatically the most energy efficient way of moving to get from point A to point B.