Very few hoof trimming issues are as controversial as trimming the bars. Opinions vary greatly, from not touching them at all to cutting them down all the way to the sole level or beyond (the Strasser method). Today I feel adventurous – you might consider me a high risk taker by tackling this issue and possibly getting shredded to pieces afterwards.

Bar tissue is identical to the hoof wall tissue, which is harder and more dense compared to the sole. Therefore bars can either support or hurt the sole, depending on their length, height and angle. In this blog, I refer to bar ‘height’ in a vertical sense, bar ‘length’ in comparison to the length of the adjacent frog and collateral grooves.

Bars are supposed to transfer energy and shock from the ground to the lateral cartilage. They are located directly below these cartilages and therefore most suitable for that task. Some time ago, I elaborated on shock absorption in “The Caudal Foot.” There might be reasons to believe that bars too short are unable to absorb any shock, especially if the horse is worked mainly over hard ground. On the other hand, bars that are too high and at the same level or extending beyond the frog or heel level can cause excessive pressure on the corium and causing bruising with resulting lameness. Some even argue that bars that are too high and too long can put pressure on the navicular bone.

A desert hoof of a domesticated horse: bars are fairly long, high and almost upright.

The old adage can get applied with bars as well: moderate pressure is good, too much pressure is bad. Or with more descriptive words: moderate pressure helps tissue growth and hardening, too much pressure causes atrophy or bruising.

At landing, a hoof should expand, especially in the heel area. That means the bars should have enough clearance before touching the ground so as to not interfere with this action and not to bruise the corium. At some point, however, the bars need to bottom out to help prevent a total expansion of the hoof capsule and contribute to the transfer of energy vertically to the lateral cartilage. Several factors determine how far the heels expand before bottoming out including: the weight of the horse, the speed of travel, the way the horse’s hooves touch the ground, the moisture content in the hoof, and the lateral hoof angles. That distance varies from 2mm to 10mm. So, on average, a relieve or taper of 5mm to 6mm for hard ground is advisable. If the horse is living and training mostly in very soft ground, then we might want to keep the bar height close to level with the hoof walls.

The bars of this untrimmed hoof are almost level with the hoof wall. This horse is living in sandy conditions and the bar growth reflects that. Like the hoof wall, the bars grow almost upright. This hoof is looking for vertical support by increasing bar height.

Not all bars grow vertically. In fact, most of them grow at an angle. Being of denser and harder material, bars can do some serious damage to the sole. Especially when bending over, we can often see bar bruising on the sole, as the photos below show us.

These bars are bent over and exerting pressure onto the sole.

Trimming the bars reveals substantial bruising of the sole. (left side of image)

Let’s stay with this photo for a moment. We also can observe white line separation and flaring on the quarters. Here comes the famous question about the chicken and the egg. Did the bent over bars push the sole to the outside and cause the flare or did the flare and white line separation happen first (for different reasons) and consequently rob the hoof of the cohesion and integrity, allowing the bars to ‘follow’ the sole wandering to the outside? What do you think?

When considering the role of the bars in hoof support, it becomes clear to me that metal shoes severely restrict proper bar functioning. Bars can fulfill their job best when a hoof is bare, using Easyboots of many kinds, using sole support like Soleguard or Equipak, or a permanent option for 24/7 support could be EasyShoes.

How far should the bars extend towards the tip of the frog and how high do we want them to be in this area? To explore this question a little more, let’s have a look at this toe crack from a steel shod horse hoof.

Do we know the cause of this crack? There are many possible reasons, could one cause be a bar that is too long?

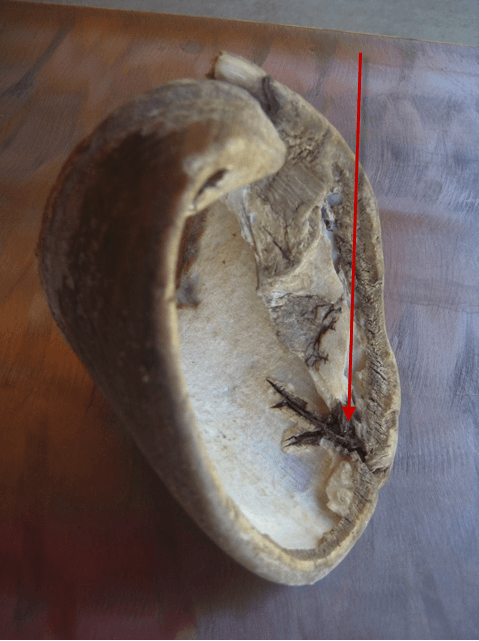

On this dried cadaver hoof, the bar has grown all the way through the hoof capsule and

exerted so much pressure from the inside onto the hoof wall that it caused the crack.

So in evaluating and examining dorsal hoof cracks, it does not hurt to examine the length of the bars at the same time to exclude this cause. Bars that are about 2/3 the length of the frog and show a taper of 5 to 10 mm towards the tip of the frog should not cause a problem as observed above.

When considering how much to trim off the bars, a few thoughts and observations might help making the proper decision:

- There is evidence that substantial sole growth originates from the bar laminae. Shortening the bars too much might impede sole growth.

- If the trimmed bars grows back substantially within a two week period, they were probably trimmed too short.

- Bars kept untrimmed and too high on a hoof with a thin sole could exert too much pressure onto the lateral cartilages and thereby push the wings of the coffin bone up. This in turn could cause the coffin bone tip (dorsal side) to tilt down even further, possibly causing toe and/or coffin bone bruising.

- Bars too high and/or too long and bent over could cause sole bruising, white line separation and possible lameness.

This list will not necessarily make it easier to decide, but it will make us think and carefully consider how much we are trimming the bars. Nothing is black and white, all is grey and on a sliding scale. It helps to ‘listen’ to the hoof.

Every horse is an individual and no two horses are identical, just like there are no two identical hooves observed among the millions of horses on earth. We trim and treat each hoof as an individual, we should judge and trim the bars in the same manner.

From the desk of the Bootmeister, Christoph Schork

As a Farrier of 50 years..and barefoot farrier for the last 40…I am overwhelmed to see the progress in boots for hoofcare. Now add thermography to show benefits to the foot with increased blood flow and we really have something to talk about!

This is very interesting observation. I’m no expert, but I keep my Arab-type horse & two mini American horses (32″ & 34″) out 24/7 barefoot (always), on grass, except when the land is too wet, & trim them myself. I have noticed that when they are on very dry, minimal grazing tracks/paddocks in summer, their feet have naturally lower bars & a shallower sole, especially the Arab who works on tarmac.The minis have feet like tough little cups- but I guess this is from considerably less weight on them :); but in softer, damp seasons, the soles become quite arched with deep frogs & very obvious upright bars, which are relatively easy to crumble away. I used to rub them off to better emulate the smooth arch of the ‘mustang’ sole, (normally I leave the sole alone) but one day decided that perhaps the formation was designed by nature to give the horse better grip in soft going- like the all-terrain tyres on my car which have a much deeper tread than road tyres to get me across damp grass. Especially as, being crumbly, the deeper bars would wear off easily rather than cause pressure. Perhaps also, when they do stand or move on harder ground between the soft areas, the air-space under the sole would help to dry the sole out? Maybe horses living (or working) in loose/deep sandy conditions might also grow a deeper ‘tread’ pattern for better grip?

Excellent article as always, Christoph! Thanks!

Comments are closed.